This is a guest blog by M. James Johnson

It was one of those groggy predawn hours, the kind where the world feels like it’s still half-dreamt. My 10:30 pm routine—listening to audiobooks as I drift off—had worked like a charm, lulling me into sleep night after night. But as Hannah Arendt narrated her Between Past and Future, her voice cool and insistent, pierced my sleepy haze around 4 a.m., she started describing how “all ends turn and are degraded into means.” That sentence jolted me awake. I can’t explain why—but it lodged there like a half-remembered dream. Not quite words, more like an echo: “…ends… means… degraded.” It lingered as I rolled out of bed, grabbed my walking gear, and stepped into the icy rain.

After breakfast, with coffee finally cutting through the fog, that half-heard whisper wouldn’t let go. It turned into a quiet itch of curiosity, the kind that scratches at you until you give in. So I did—typing into a Grok search, “What does Hannah Arendt have to say about means and ends, or ends and means?” Grok fired back: “In Between Past and Future, in Chapter 8…” and continued several pages with too much information for 6:30 in the AM. But my “Withdrawn from Junior College District of St. Louis County Library, St. Louis, Missouri” 1961 edition of Between Past and Future, retrieved from the shelf mid-sip, only had 6 sections, not even chapters. The mismatch landed like a splash of cold water… right on the nose. Disorientation, sure—but the fitting kind, the sort that mirrors our whole unraveling moment. I’d caught a glimpse of something about Arendt’s means to an end that was raw and true, even if I couldn’t nail it down yet: a pattern of collapse thrumming just under the skin, more a bone-deep hunch than tidy footnote.

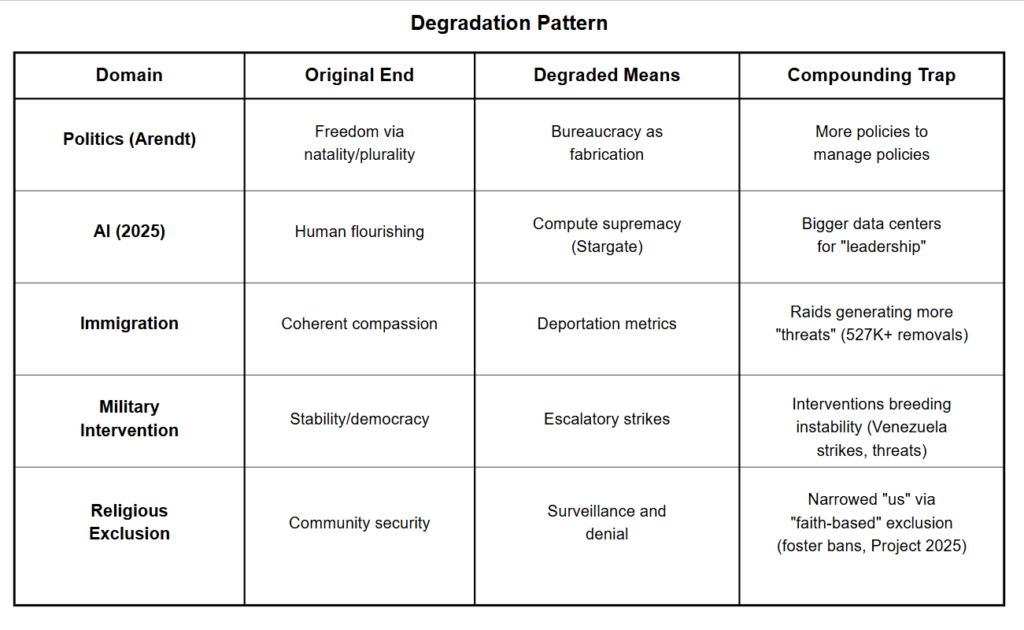

What I sensed was this: innocently installed ‘means’ create diffusion, dilution, and detachment from intended goals. But there’s a fourth stage I didn’t see at first—capture. The means don’t just replace the ends; they imprison us. We become unable to imagine alternatives because we’re trapped inside the logic of the means themselves.

And here’s the tragic irony that compounds the problem: when meaning drains away, we don’t stop and reconsider. We intensify the means. More infrastructure, more force, more optimization. The acceleration itself becomes evidence that we’ve lost the plot entirely.

Three cases prove this isn’t isolated to one domain—it’s a structural pattern in how instrumental reason consumes itself, even capturing those who claim the name of Christ ?

Arendt: When Political Action Becomes Fabrication

Hannah Arendt diagnosed the collapse of genuine political action when we adopt “homo faber’s” ( man the maker/craftsman) logic— treating politics like fabrication, like building things. In The Human Condition, she traces how this destroys what makes politics political: “natality” (the capacity for new beginnings), “plurality” (the irreducible “who” of each person), and the space of appearance where freedom is enacted.

The mechanism is subtle. We begin with a genuine end: freedom, justice, human flourishing in the public realm. We adopt seemingly practical means: laws, institutions, processes. But fabrication’s logic is instrumental—everything becomes a means to an end, which itself becomes a means to another end, endlessly. The original “for the sake of what” dissolves.

– Diffusion: Energy scatters across competing instrumental priorities.

– Dilution: The original vision of freedom becomes vague, rhetorical.

– Detachment : Finally, complete disconnect. We’re building systems to maintain systems, writing policies to manage policies—what Arendt called “curious ultimate meaninglessness.”

The compounding trap: when politics feels meaningless, we install more bureaucracy, more procedures, more technical solutions. This intensification proves we’ve already lost genuine political action, which would have been freedom enacted now, not achieved later through instrumental means.

AI: When Human Flourishing Becomes Synonymous with Computational Power

The pattern repeats in our AI moment with startling precision—and it’s a sobering warning for the church. Once again, evangelicals and others chase technological dominion under the banner of stewardship, echoing the Cold-War logic that framed nuclear superiority as responsible dominion over creation. The stated end remains noble: AI for human flourishing—breakthroughs in health, climate solutions, creativity unlocked. But we adopt the same innocent-sounding means: build ever-larger computer infrastructure, concentrate ever-greater power, all to “stay ahead” of rivals and maintain technological leadership.

By December 2025, the drift is complete. The end (human flourishing) has degraded into a means (technological supremacy), which becomes its own end (not losing to China), which justifies any means whatsoever. Open AI’s Stargate project—a $500 billion juggernaut with partners like Oracle and SoftBank, now under construction at sites in Texas and Michigan—exemplifies this: fortified campuses drawing gigawatts, razor-wired against intrusion, nuclear-adjacent like Amazon’s expanded Talen Energy deal for 1,920 megawatts.

Once again: Diffusion: Resources scatter toward infrastructure arms race rather than applications.

– Dilution: “Human flourishing” becomes a marketing ploy; the real measure is teraflops and training runs.

– Detachment: We’re building data centers to justify building bigger data centers. The U.S. now hosts over 5,000 such centers, consuming about 4% of national electricity. For what? To stay ahead. Of what? Other builders.

The compounding intensifies: when anyone asks “why?”—when the original purpose becomes unclear—we double down. Build bigger. Build faster. Pour copper and rare earths into monuments to means without ends. The question “for the sake of what?” becomes unanswerable, even embarrassing. And in Christian circles, this frenzy echoes the old temptation: dominion through mastery, as if God’s image-bearers are perfected by silicon, not the cross.

Coda: The Pattern Captures Us Now—and the Church with It

This isn’t just theoretical or technological—it is happening across every domain in December 2025, and we are captured by our means. Worse, the backwash of Christian nationalism drags diverse Christian persuasions into the same vortex: ends like “biblical justice” or “kingdom values” diluted into metrics of power and exclusion, all while claiming divine mandate.

Consider the pattern laid bare:

In each case, the same mechanism: original ends that were hard to measure (security, democracy, coherence) get replaced by means that are easy to count (deportations, strikes, exclusions). The metrics replace the meaning. Immigration’s end was border security, national coherence, perhaps even compassion through order. The means—ICE raids, mass deportations, family separations—have become the performance itself, with over 527,000 removals year-to-date. We measure success by numbers removed, not by any coherent vision of what we’re securing for. The deportation machine generates its own necessity. We’re captured—and too many pulpits bless it as “God’s border.”

Military intervention: The end was democracy, stability, stopping drug trafficking. The means—strikes on smuggling boats, escalating control and now threats of incursion into Venezuela—become self-justifying. Intervention creates instability requiring more intervention. The logic is closed. We’re captured, with Christian nationalists framing it as a holy war against “godless regimes.”

Religious exclusion: The end was security, perhaps community coherence. The means—surveillance, denial of services in foster care to LGBTQ+ families, exclusionary policies under new Trump orders echoing Project 2025’s “biblical principles”—become the definition of who “we” are. The exclusion itself captures us, narrows us, makes us unrecognizable to our stated values—yet it’s preached as fidelity to Christ.

When the hollowness becomes unbearable, we don’t stop—we compound: more raids, more strikes, more exclusions. The acceleration itself is the symptom of advanced capture, and the church, in its nationalist streams, leads the charge.

The Kingdom: The Only Way Out

Stanley Hauerwas’s reading of the Gospel offers something more radical than “use better means” or “clarify your ends.” The Kingdom of God, he argues, cannot be made, organized, built, or achieved. It cannot be earned by religious effort, imposed by political struggle, or projected in calculations. “We cannot plan for it, organize it, make it, or build it… It is given. We can only inherit it.”

This isn’t passivity—it’s a complete refusal to play the means-ends game, a direct rebuke to the fabrication that Arendt decried and the compute crusades that now seduce the faithful.

The reason the Kingdom resists instrumentalization is that “scripture refuses to separate the Kingdom from the one who is the proclaimer of the Kingdom. Jesus is Himself the established Kingdom of God.” The Kingdom isn’t a future achievement requiring proper means; it is present in Jesus’s life and cross, requiring only recognition and participation.

This is why, as Rauschenbusch wrote, “Jesus deliberately rejected force and chose truth… Whenever Christianity shows an inclination to use constraint in its own defense or support, it thereby furnishes presumptive evidence that it has become a thing of this world, for it finds the means of this world adapted to its end.”

The cross wasn’t a means to the Kingdom, not even the way to the Kingdom—it is the kingdom come. Because the cross reveals the social character of Jesus’s mission: a new possibility of human relationships based not on power and fear, but on trust made possible by truth.

Peter’s confession at Caesarea Philippi captures the pattern we’ve traced: he names Jesus as Messiah but assumes this means worldly power to restore Israel’s preeminence. Jesus rebukes him: “Get behind me, Satan! For you are not on the side of God, but of men.” Peter had learned the name but not the story that determines its meaning. He had innocently installed the means of empire to achieve the ends of the Kingdom—but those means would have transformed the end into its opposite.

The pattern is everywhere: Arendt’s political action is consumed by fabrication’s logic. AI’s flourishing is devoured by compute supremacy. Contemporary America—and its captured churches—is ensnared by enforcement, intervention, and exclusion. In each case, the remedy seems to be more—more systems, more infrastructure, more force—accelerating the very meaninglessness we’re trying to escape, all while waving crosses at the chaos.

The Kingdom offers the only exit: stop trying to achieve it. It’s already present, requiring a different posture entirely—not building or forcing or optimizing, but participating in a reality already given. A community based not on the fear that generates moats and raids and escalations, but on trust made possible when “our existence is bounded by the truth.”

That truth, as Rauschenbusch saw, “is robed only in love, her weighty limbs unfettered by needless weight, calm-browed, her eyes terrible with beholding God.” It asks no odds. It needs no spears or clubs or data centers to prop it up. It simply is—and invites us, the church adrift in nationalist backwash, to stop running the race we’re already losing, to step out of capture, and to inherit what was never ours to make in the first place.